Dick Fosbury: The Revolutionary Who Turned the High Jump Upside Down

A remembrance by Ed Hula

Dick Fosbury was an unassuming revolutionary at a time when the U.S. and the world heaved with protest. In 1968, the Vietnam War, civil rights, assassinations and other events fueled foment and cries for change.

Fosbury, a 22-year-old engineering student in Oregon, may have sympathized with the causes of student protests but that was not the revolution he would lead. Instead of polemics, athletics was the means to the end for Fosbury. In this case, a gold medal in the high jump at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City.

Fosbury will forever be remembered as the first gold medalist to use a new technique dubbed the “Fosbury flop”. Gliding over the bar headfirst, the technique quickly replaced the scissor-style jump with the feet going first. He did not claim to be the inventor of the new jumping style, but the Fosbury flop is how it remains known. With the encouragement of his high school coach, Fosbury began experimenting in the 1960s with a dramatically different approach to the high jump. The head first technique took a few more years to develop, but by the time of the 1968 Olympics, he was on his way to number-one in the world rankings.

The “flop” has become the only style followed by jumpers since the 1972 Olympics, the last to with a gold medalist using the now archaic scissor-style jump.

“To be honest, I wasn’t thinking of being a revolutionary,” he said in 2018 on the 50th anniversary of his Mexico City triumph.

“My intuition, my natural instinct helped me to find a better way, a new way of jumping. I happened to be the only one using it at that point. Who knew that after the gold medal in Mexico City kids around the world would adopt this technique because it looked fun,” he said.

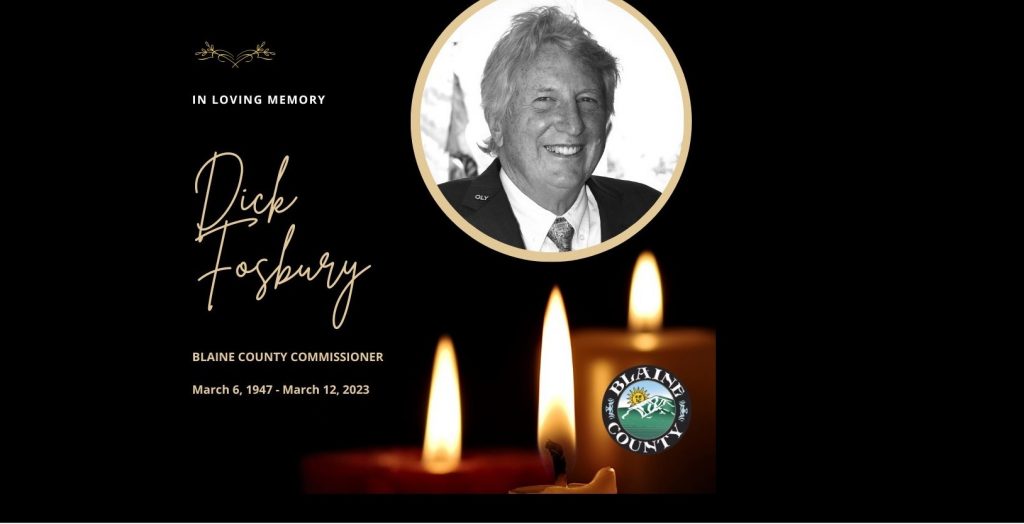

Fosbury died March 12 in Salt Lake City where he was being treatment for lymphoma, which was first diagnosed in 2008 . He had just celebrated his 76th birthday. He lived in Bellevue Triangle in southern Idaho.

Fosbury’s survivors include his wife Robin Tomasi; sister Gail Fosbury; son Erich; stepdaughters Stephanie Thomas-Phipps and Kristin Thompson as well as grandchildren.

After he won the gold medal in 1968, Fosbury says he had to give up the high jump as a condition for readmission to Oregon State University. He blamed the time spent perfecting his jumping technique instead of school work for the academic disconnect. Upon graduation, the Oregon native would settle in southern Idaho.

Fosbury launched a civil engineering firm in Ketchum, Idaho, while staying active in Olympic circles. He was happy to coach athletes in workshops around the world. Fosbury was inducted into the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame in 1992.

He ran unsuccessfully for a seat in the Idaho state legislature before becoming a member of the Blaine County Commission in 2019. He was elected to a second term in 2022. A Democrat, Fosbury’s seat will be filled with a Democrat to be named by the Idaho governor.

“Dick was truly a remarkable individual and I consider it an honor to have been able to have worked so closely with him for the past almost six years and witnessed first-hand his dedication and commitment to serving others,” says Blaine County Administrator Mandy Pomeroy.

“He was such an inspiration to everyone around him and my life is better off for having known him,” she says.

A black drape covered his chair and vase of flowers placed on the desk at the March 14 commission meeting. Fosbury was one of three county commissioners for Blaine County, population about 25,000.

Pomeroy described the session – packed with an array of county business – as “difficult”. She says her office is now inundated with media requests as word of Fosbury’s death spreads.

She says a memorial will be planned, perhaps in a couple of months.

Fosbury was involved for years with the U.S. Olympians and Paralympians Association as well as the World Olympians Association. From 2007 to 2011 he was president of the WOA.

“Dick will be sorely missed. He was a good friend to us all and a real advocate for the core values of the Olympic Movement. I was honored to work with him both at the WOA and at Peace and Sport,” says Fosbury’s successor Joel Bouzou, the current president of WOA.

Fosbury acknowledged the influence the 1968 Olympics cast upon him as he entered adulthood in the turbulent year that was 1968.

“Mexico City was a new experience for me. It changed my whole perspective when I started to observe athletes from all the different countries,” he told this reporter in 2018.

“Different languages, different races. Different food. It really was a transforming experience for me. We all have the same desires and commonalities regardless of what the politics are,” said Fosbury.

He raised his fist at the medal ceremony in solidarity with sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos, whose podium protest earlier in the Games triggered wild controversy in the IOC, USOC and beyond.

When he returned to the U.S. he travelled widely to talk about his experiences at the Olympics. The protests by Smith and Carlos were of interest wherever he went.

“Every cab driver would ask me about the Black Power salute and I would explain this was not about Black Power. This was about the Olympic movement for human rights. It’s not black or brown or red or yellow or white. It’s for human rights,” Fosbury said.

Fosbury tells his story in detail in a 2018 book, “The Wizard of Foz – Dick Fosbury’s One-Man High-Jump Revolution” written with Bob Welch, from Skyhorse Publishing.

An optimist about the power of sport to help make the world better, Fosbury also understood the realities of life.

“The Olympics and sport represent our culture and society. And so we constantly see the improvements and great performances by the athletes and that’s very exciting. At the same time we face challenges with doping, corruption, usually influenced by money.

“So even in sport we face the same challenges we face in politics, business. It’s complex, it’s confusing. But I am a true advocate of the power of sport to be a positive influence on people,” said Fosbury in October 2018.

It was the last time we had the chance to speak.

Written by Ed Hula